Inside Palantir: Profits, Power & The Kill Machine

We spoke to a former Palantir employee, now turned critic, agitator and educator speaking out against the tech company.

One of the most defining images of Trump’s second inauguration was the tech overlords filing up to declare their allegiance. Perhaps this line up was a demonstration that they wield great powers too.

But in contrast to the loud presence of Zuckerberg, Musk, Pichai and Bezos, there were a few notable figures who were absent from these festivities but are no less significant: Peter Thiel and Alex Karp.

Thiel, Karp and their data analytics company Palantir have managed to fly under the radar a long time, whilst pulling strings in Washington, and playing a significant role in propelling Trump to a second presidency. Thiel in fact endorsed Trump even in 2016, donating to his campaign. This time around, Alex Karp donated to Trump’s inauguration fund, giving him $1 million.

Palantir’s work in defence, surveillance and warfare has enabled it to operate in the shadows, dealing directly or tangentially with sensitive state records. But more than that, the secrecy it maintains is a PR-exercise to create a god-like mysticism and cult status around its work and leadership, along with being a PR-strategy designed to keep us confused; making it hard to criticise and hold it accountable.

But despite operating in shadows, the company is far from obscure. It is entrenched in the US government, having bagged contracts across departments since the very start. In fact, it has received $113 million in federal contracts since Trump came into power a second time.

On the surface, what Palantir’s technologies do is data integration and analysis. But this description obscures the nature of its work, given the use cases and contexts its technologies are deployed in.

Palantir is a company currently enabling Israel’s genocide of Gazans by supplying it intelligence and surveillance tools. It is a company that has helped ICE separate immigrant children from their families in the US. It now has a new deal with the Trump administration to provide real-time tracking of migrants. It is a company whose ex-employees are now to be found working for the federal government inside DOGE, mishandling sensitive federal databases. And it is also a company handling one of the largest health databases in the world, the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) records.

Last week, I was introduced to a former Palantir employee, who has now turned critic, agitator and educator speaking out against the company.

Juan Sebastián Pinto used to write about architecture. He went on to develop an interest in digital architecture, which is when he got fascinated by Palantir. In 2021, he joined the company as a Content Strategist. Eventually he left Palantir for another job. But it was the use of Palantir’s technologies by Israel in Gaza post the October 7 attacks, and subsequently its proximity to the second Trump administration, aiding the targeting and deportation of immigrants, that forced Juan to speak out.

Juan’s journey has been an interesting one. He used to draw the Kill Chain diagrams that visualised Palantir’s technologies, which includes ISTAR technology, used in various conflicts and crackdowns around the world. He is now alarmed at finding such technologies being deployed a lot closer to home, like at the immigration protests that have erupted in Los Angeles in the last few weeks.

We spoke at length about his motivations behind joining Palantir, the company’s founders, workplace culture, and problematic record, his disillusionment as a worker in the tech industry and why he decided to speak out against Palantir now.

Juan is now part of the anti-war movement in Denver, speaking out against the use of Palantir technologies by the state of Israel. They are demanding that Palantir cut all ties with Israel, and end all contracts with “entities that use Palantir’s software to violate human rights”. During one of these protests, Pinto did a speech in front of the Palantir headquarters. He is writing about the misuse of AI technologies here.

Below is an extract from our conversation, which has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Manasa: In the context of Palantir and its technologies, what would you say are the top three terrible things we should know about?

Juan: To me, the biggest concern is that people talk about AI as a monolith. As one technology with a linear path, that is inevitable, taking us towards singularity; where machines become smarter than us, potentially taking away our ability to produce labor. People focus a lot on that, and the issue of these technologies helping develop chemical and biological weapons that could be really dangerous. But I think one of the main dangers of artificial intelligence is exactly what Palantir has spearheaded, which is ISTAR technologies — intelligence, surveillance, targeted acquisition and reconnaissance technologies — also known as the AI-assisted Kill Chain. They've given it many different names, but the idea is these highly sophisticated and advanced dragnets and systems for collecting people's information, integrating it in order to identify targets, triangulating personally identifying information using huge datasets derived from the commercial sector, from governments. These technologies are not only a central part of armed conflict today in places like Ukraine and Gaza, but also central to the policing that is unfolding in the United States right now. This militarized vision of tracking individuals for deportation.

Recently I saw predator drones were being flown around Los Angeles in circles to track and potentially target protesters. You know, I used to spend a lot of time drawing these kill chain diagrams, which involved all the information that gets collected by drone systems, distributed ground operation systems, and satellites, which is used to target and execute individuals in warfare. I drew these diagrams and how the information is shared to make decisions about killing people, and I see the same kind of arrangements happening in LA with the drones, turning the city into a connected, digital battlespace. To see these technologies — dangerous and very advanced tracking, surveillance, reconnaissance, execution technologies — so close to home is probably our biggest danger.

I think it's very possible that Palantir software has already been used unconstitutionally to track people based on their protected First Amendment activities, such as social media posts. Recently, a few students were notified about deportation because of what they wrote.

So yeah, I'll give you the three things: one, the increasing prevalence of these targeting technologies as a leading use case for AI, and second, the fact that we're not talking about it even though we see it at war and at home too. Third, the normalization of all this militarization of the commercial sector and the public sector.

I think companies like Palantir participate in normalizing this kind of overwhelmingly data-hungry vision of the world, where surveillance and total control fuels success and advantage, where victory must be achieved at all costs.

Eisenhower in his farewell speech way back in the day, but not too long ago if you really think about it, warned Americans of the prevalence and encroaching nature of military doctrine and technology on the fabric of American life. I think we're experiencing it right now, where the leader of a company that spearheads the development of advanced tracking, killing technologies [Alex Karp] is considered the Economist CEO of the Year, a man who constantly talks about executing journalists and critics, including by using covert assassination methods like fentanyl poisoning. The fact that this kind of a company is respectable, seen as not only leading in the field, but as an example for so many. That really scares me about the future of this country, where everyone's at risk fundamentally.

Manasa: You used to work for Palantir, and now you are involved in this political action against the company, primarily because of its involvement with the Israeli government, and also for Palantir's technology being used in perpetrating violence against vulnerable communities within the US, like against immigrants. So what happened there, between you working there and you now being involved in political action? Could you tell us why you got involved in the anti-war movement?

Juan: The reason I'm involved in a lot of education is because that's the process I had to undergo in order to speak out and be confident speaking about these topics. So that's why my focus is so much on education, because it was while working at Palantir that I started watching Adam Curtis and his documentaries about the critical history of Silicon Valley, the ideological origins of a lot of the belief systems and ambitions that are held very close there. I think that was the beginning of my ‘radicalization’. This era, post pandemic, was very meaningful to me. So when I had an opportunity to leave, I did.

[When I left Palantir] I still had this belief that these technologies were inevitable, that I was just working at the most prestigious company in the field, and that I could continue working with leading people and companies because of this experience. So I wasn't too critical of it, but later I would read up on Andrew Cockburn’s work on killing technologies, Jathan Sadowski work, and Edward Ongweso Jr.’s work. And eventually learned a more critical perspective.

How this is actually not something new: IBM and other companies have tried to implement data assisted ways of executing warfare for many decades, often showing that these ways to conduct warfare, these kind of decapitation strikes like the ones you're seeing in Iran now, can often lead to way more problems than one could ever anticipate. It breeds more conflict, more resentment in the places where it's deployed. It leads to incredible amounts of civilian casualties. It helps develop and push the development of highly invasive, ISTAR tracking technologies using artificial intelligence that are later commercialized. So I gained a very critical understanding of that.

And then, boom. As soon as I saw the reaction to October 7th [attacks], the aggression in which these technologies were used for more than a year in Gaza is scary, unprecedented. That's when I started writing, seeing the images of UN facilities, schools, hospitals being annihilated by these technologies, which are supposed to be more humanitarian, more direct. The prolonging of the conflict for so long, the images of the flattening of Gaza. It was just too much for me personally.

And I had been writing about kill chains and AI and the dangers of that, but really it just became super scary once Trump started. He secured the nomination and the presidency, and Palantir was sponsoring his events. Karp donated a bunch of money to Trump's inauguration, and then I saw executive orders coming out nonstop that seemed to be just laying a red carpet for Palantir to fulfill its mission of unifying government siloed data and making it more efficient, And the directive of DOGE is basically what Palantir does, which is unifying data silos. And I was like: it's only a matter of time until Palantir is jumping on these contracts. And it was, that's why I started writing about it.

I have the rare position of having been an insider. It's an important thing to speak about. One might not be able to speak about these things in the near future. And the way I see Palantir handling the conversation, not responding to journalists, not making clear statements about whether its software could be used unconstitutionally, not engaging in a transparent and clear discussion with the public about its technologies, and instead shrouding it with marketing showmanship and tactics of public relations. I don't think they're fulfilling the responsibility as a leader in these technologies.

Manasa: With Palantir a lot of this is not new though, is it? Palantir’s record has never been clean. Even if we go back to something like 2017, Palantir was helping ICE target undocumented immigrants in the US. They were using unaccompanied minors crossing the borders to locate their parents in the country. And Palantir was enabling ICE again in 2019, helping ICE separate immigrant parents and children. So I'm wondering what is it specifically about this moment that made you speak out against the company? Is it the urgency you felt like you said with Trump's re-election?

Juan: First of all, I'll say, regarding those two things you mentioned, and there's even more horrifying stuff that was available when I joined, that I just didn't look into. The HB Gary stuff with Glenn Greenwald and how they tried to discredit journalists (Note: Palantir was linked to a security firm called HB Gary that was exposed for its attempts to attack Wikileaks and its supporters, including journalist Greenwald), and me being a freelance journalist. I should have paid more attention to that.

But you know, there's this rationalist argument that Palantir is very good at deploying. It comes from this fantasy of being a talented, gifted genius, therefore you understand the world better, And a lot of people that are high IQ or very intelligent, accomplished in their field, are susceptible to flattery and in-group thinking. That's exactly what happens at Palantir, there's a sort of culture developed from the top-down where there's some sort of canned FAQ response to any ethical question.

That is developed by a team that supposedly cares for civil liberties, but in my opinion, serves more of a public relations function, internally and externally, to sort of qualm beliefs that, ‘Oh yeah, Palantir does really dangerous stuff by nature, but we have this group of people here who are devoted full time to thinking about it’. And you can bring it up too, in our chats, that was the culture. My understanding is that they're addressing dissent differently now, splitting people into groups and going after small groups of people, instead of addressing the company as a whole. But that's a separate discussion.

What I'm saying is they have a playbook, and it's operationalizing language itself. It's turning language into sort of a mobilizing and motivating in-group forming tool. And Karp is himself a very well read and studied expert in the manipulation of language and the use of language to channel the aggression of groups, the resentment of groups. And I'm not surprised, I practically expect that some of these sort of tactics that he studied, he uses on his own employees in order to build a kind of a cult like personality and leadership style.

So then there's the technical level, Palantir, before, for example, didn't work on Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) which is the removal part of the process that ICE engages in. Like, the literal physical mobilization of people. Because, allegedly, they didn't want to participate in separation of families. But now they do. Now they complete the full cycle of targeting, mobilization and deportation. And this is turning back to the worst impulses of this technology.

My biggest problem is seeing Trump take over. It feels like these technologies are becoming mainstream in the commercial sector and in our public life, and could be weaponized against us. And that's what scares me.

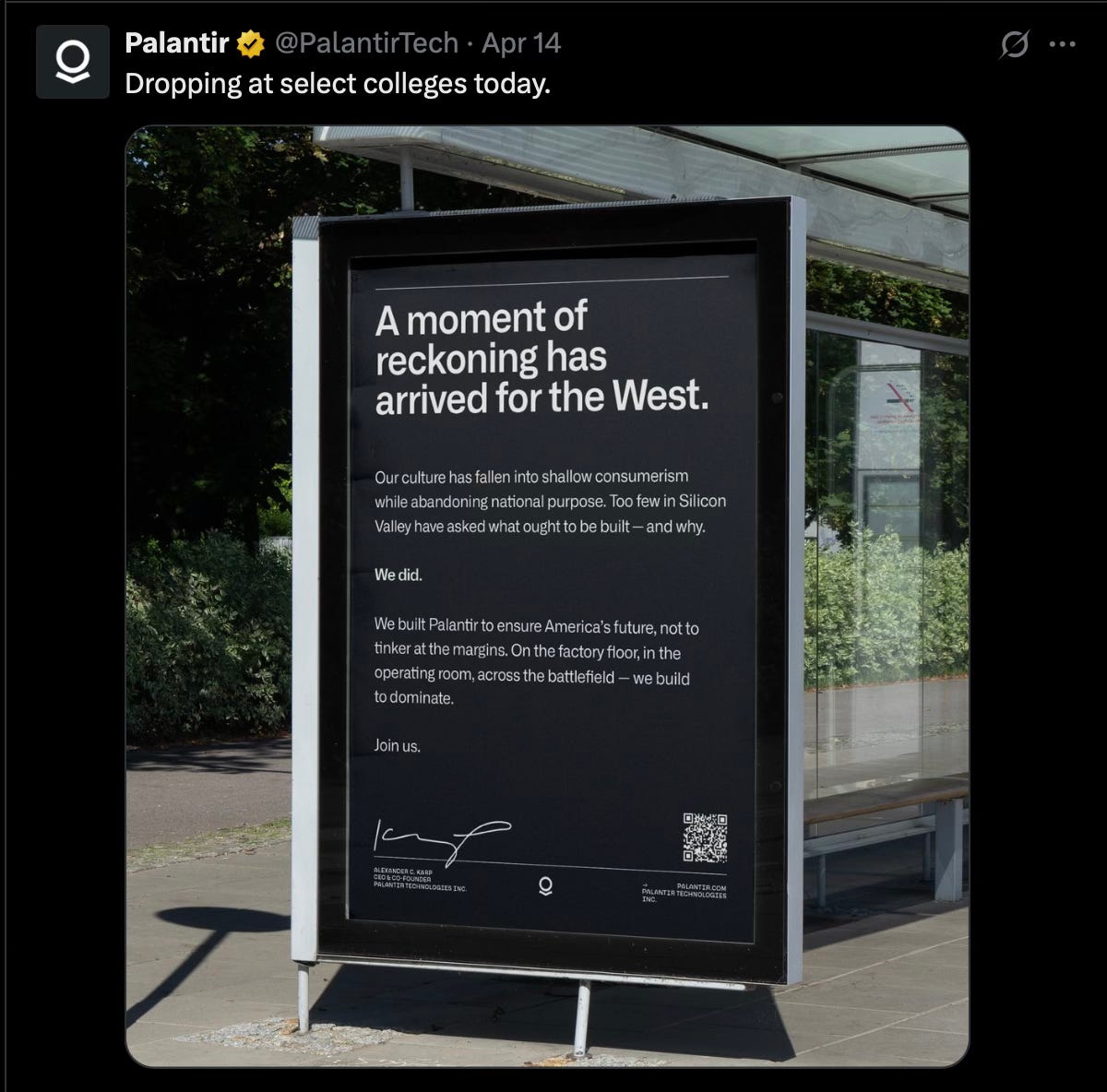

Manasa: I mean, with Karp and the workplace culture - now he's coming out publicly and very explicitly saying, if you have a problem working for a company that's helping perpetuate militarized violence in these other countries, then don't come work for Palantir, right? So, I mean, he is an interesting figure, because when you listen to him, a lot of rhetoric is one of grandeur, sort of painting this picture of Palantir that it's on this huge difficult mission, but it's doing important work in these “dark times”. And there is all this patriotic language that Karp uses, almost making it seem like the services his company provides is almost a public service, helping the government with its national security interests.

And on the other side, he would also go and very openly admit the company's technology is being used to kill people; that this militarization and commercialization of defense is really good for Palantir's business.

So on the one hand is the rhetoric that they are doing this for the good of the United States, and on the other side, being very open about the kind of profit they make from all of this violence. How do you square that?

Juan: I think fundamentally, they misunderstand core American values. Because I think as a whole Palantir and the artificial intelligence industry, especially those focused on targeting technologies, are on a massive scale, challenging our First Amendment rights and our Fourth Amendment rights by establishing so much surveillance and digital policing across our cities and governments, even before we have a chance to speak out, delimiting what we can say, even what we can think, by turning the world into such a surveilled, tracked environment.

So they are undermining core constitutional principles, by supporting the Trump administration, which to me is the first reason I spoke out about this, to be honest. I was enraged because I saw Musk make a sexist tweet, and I was like, how is Musk in charge of [DOGE] that is supposed to reconfigure our entire digital infrastructure, connecting our siloed data and bringing in talent here? How am I supposed to trust an individual like that, who is so, you know, dismissive of women, of homeless people, of people who struggle, and are disadvantaged? As the richest human being in the world... I was like, it's crazy to me that people aren't even having this discussion here in the Palantir group.

I think, more directly, when I was in Palantir there was always the question about when it was appropriate to leverage patriotism or the flag and marketing, and I've seen a lot of the boundaries we had back then be completely ignored. Now, I think it's a wholesale prostitution of America and its values in order to sell weapons. And increasingly profiteer on this stuff.

Manasa: But what would you say to this contrasting picture of Palantir claiming to be this almost God like entity that is doing this amazing work, versus then also admitting how it's a killing machine. You know, how is it possible to hold both these public images?

Juan: I think the hypocrisy serves a purpose in itself, right? Because it leads to greater confusion, and a lot of conflicting statements allow you to create conditions where someone who's joining the company can look elsewhere for examples of good work they do, or to justify their work, or statements that are different. You know, fundamentally be like, ‘Oh, they must be dealing with really hard problems that they're talking this way.’

For a lot of the people that work there, if our time was when we were developing the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb, they would want to be involved. Because it's more important for them to be involved than not to be involved, right? If there are consequential technologies being developed… And that was part of my reasoning as well, I would want to be in the room that decides how these technologies are used. But that also leads to greater realization that a lot of other former employees had. It's like, we are making decisions here in this company that probably should be made outside of this company.

When we design a lot of these systems for governance automation, we're making explicit and implicit decisions about the quality of the data, the accuracy of the data we take, whether it's representative of the problem we're trying to solve, whether the use case adequately solves that problem, whether the metrics we collect are accurate, whether these models train correctly. Those decisions are made in a private organization like Palantir, but could later influence the outcomes of people's lives.

Here's another super clear example: they talk and they say, transparency, transparency, transparency, right? But again, all the material they publish seems to be almost unreadable and difficult to parse, almost intentionally. So they say they're not a data company, which is ridiculous. Because according to them, they don't sell and collect data themselves to save on their own servers or potentially give to other people. And one, while that might be technically true, they do work with data brokers who use their platform. And two, more importantly, it's not about the data. To me, it's about the capability to exploit data, and that's what they are really good at. Graphing this information to find unknown trends, patterns, issues and solve them.

Manasa: It's important you brought out the aspect about data, because Palantir was already a major concern for those who are worried about a private company having a monopoly over public sector contracts. Because since the beginning they were bagging a lot of US government contracts across departments, which helped them to grow and become so big. But now there is concern about them gaining a monopoly over people's data.

Is this worry about the company’s involvement with DOGE, which has managed to capture a lot of federal databases since Donald Trump’s re-election?

Juan: I think that's a great question. And again, while they might not be building or collecting this data themselves for their own purposes, they are claiming a monopoly over decision -making, AI assisted decision-making across the government, and so many periods kind of woke me up to the need to speak out.

I'd already been publishing the stuff I wrote about the killing applications in Gaza, and I still woke up in the middle of the night a few months ago remembering I named, branded, designed and wrote the first white paper for this platform called Palantir Fed Start. Palantir Fed Start is supposed to help startups and new ventures gain access to government contracts and the ability to bid on them fast, without the need to go through the long and tedious accreditation processes and standards that they used to have to go through before. Because instead of building their solutions on their own infrastructure and what not, they built it on top of Palantir accredited infrastructure and are able to ship their solutions faster to the government. I see DOGE has created this enormous opportunity for companies like Palantir and other tech companies and startups to plug in the holes left by the firing of so many federal employees through the creation of these initiatives. And they're using platforms like FedStart to go after federal contracts including a lot of unproven technology. I saw Anthropic and Google are pushing their technologies, potentially their chatbots like Claude into the government using Palantir FedStart. And the kind of moral dissonance that I see in these industries is bordering on the ridiculous.

You know, Dario Amodei. He's the lead of Anthropic. He's considered in the media, because of his supposedly ethically-minded comments, to be leading the most ethically aware operation in artificial intelligence and in the LLM field. He talks in interviews warning people about the bloodbath that's going to happen in the jobs marketplace, the imminence of replacement of human roles by unproven, untested technologies. Yet at the same time, he is capitalizing on the opportunities created by companies like Palantir, with [entities] like DOGE, to serve as the agent of that bloodbath itself by selling his technologies to the government when they are unproven.

And I see all the issues that the people at Anthropic itself have been talking about lately. LLMs blackmailing their users in test environments, potentially coming up with weird scenarios to stay connected or online. The [AI] hallucinations that we saw in the reports in RFK Junior's Health Department. The risks are enormous, yet the desire for profit and for growth that guides a lot of these companies is so extreme, they're willing to not only capitalise upon scenarios such as those enabled by DOGE — where thousands of civil servants are deprived of their jobs —but also where these companies will push indiscriminately these untested technologies for use in governance.

I wrote the first white paper advocating for this stuff, not understanding the way in which it was going to be almost orchestrated in the end, as a sort of a forced takeover on American institutions by these private interests, facilitated by platforms such as the ones I helped brand. And more importantly, all these statements about fear are just to bring attention, just to bring investment. I'm very disillusioned by that as a tech professional.

And the last thing I am going to say is imagine the antitrust conflicts of interests here, right? When you're talking about a company commanding a lot of the infrastructure to hold and communicate data across government silos but also working with a bunch of startups, a lot of which it has equity stakes in… Palantir Fed Start is often sold to these startups by these startups giving equity to Palantir, paying some high fee to Palantir. So in a sense, Palantir has interest, not only within the government, and within potential future vendors and sellers, but across the entire tech ecosystem.

Who does Palantir serve at that point, right? Is it its customers? Is it the users of the software and the government? Is it the citizens that are subject to the effects of these decision making systems? Or is it just the startups in which it might hold equity in?

Manasa: That’s very interesting. Especially the last point about their stake in all these new startups and their financial interests in all of this.

I mean the difference in what is said by people at Palantir, and what happens is always so contrasting. Even Peter Thiel, he claims to be a libertarian, and is someone who explicitly talks about replacing state power, and yet Palantir works with the state, and they have so many contracts with the state, and they have so many connections with the political establishment at this point, including Peter Thiel, previously even donating to Trump's campaign. So what should one make of Palantir? Is it then, just as simple as Palantir doing whatever is financially beneficial for itself, and that could include any means of grabbing political capital, and then through that, whatever monopoly they can establish in the tech industry?

Juan: I'll just answer pretty briefly, because I think it's good to answer this question briefly, because it is kind of simpler than you think. I think most people who have worked with Palantir, and especially former employees who have spent a lot of time in the philosophical rhetoric behind it, behind the founders, their books, I think everyone comes to the same conclusion in the end, and that is:

In practice, the only pattern of behavior that we've seen from Palantir leadership has been to be as close to the center of power that is currently established as possible; with any means necessary.

That's why they've gone after traditional centers of power in Europe, in the United States, participating in Davos, always working with Fortune 500 companies, almost largely targeting those working with any administration, donating across party lines. I think it's in their interest to set up the chess pieces, in order for them to be in the most advantageous position under any given administration, under any given scenario, regardless of the political beliefs or objectives of the administration or the centers of power. It's kind of a disappointing answer…

Manasa: No, not at all. I think you capture it perfectly. It's not disappointing, it's just what it is. It’s always interesting with Palantir, because they try a lot to have all this storytelling around their work, but when you boil it down, it's as simple as that.

Coming back to data in addition to government databases in the US, in the UK now, Palantir runs the data system that governs our national healthcare, the NHS. So it's a big, private American company that helps perpetuate all this militarized violence, and is kind of the digital arm to Trump 2.0 data capture, that has a huge contract now to handle sensitive health records of everyone in the UK, the whole population. How does that happen? It seems really bizarre to me, given the history of the company and the kind of company it is, versus the fact that this is social healthcare in the UK.

Juan: I think obviously people are waking up to the consequences of that in the UK, and a lot of hospital trusts have begun speaking out about the need to develop their own sovereign, independent solutions. IT systems to solve the problems that their doctors and their staff have identified as actually needing attention, as opposed to like this, federalized one stop shop solution for all the different healthcare systems and trusts in the UK. So I do like a lot of the advocacy that's coming out of the UK, because I think they've kept a lot of the fight against companies like Palantir alive, by putting this issue up front and center. So in that sense, I am grateful for the work a lot of activists in the UK have done.

I think again, Palantir, is really close to centers of power, and it accomplishes a lot of selling of its software under conditions and under emergency scenarios, or by selling and offering its platform for really cheap or for free, in trials or pilots, and oftentimes through secretive meetings, with small groups of people in the conversation, as opposed to the stakeholders that are actually involved.

Manasa: I mean you're right. The NHS Data contract during COVID that Palantir got, it was an “emergency” contract, which initially cost just £1.

This is my final question. And let's come back to your action against Palantir. What do you want to achieve right now with anti war movement in Denver? Why should people care about Palantir and what it's doing?

Juan: Two things. I'm an immigrant. And I'm a freelance reporter.

I've always been very interested in covering topics that are hard for people to understand. And I did that when I worked with architects. I did that when I worked in tech. I'm going to just keep on doing that today. Helping people understand complex things that influence their life. I find that the most important thing for people to understand today is how tech interacts with our civil rights, and is potentially violating our civil rights. How a lot of these situations we find ourselves in are only possible because of technologies developed within the last decade or so. How there's still time to be able to change that.

And fundamentally, as an immigrant, as someone who came to this country, had a great experience and education here, I believe that America's legacy in the world should be to push the envelope on civil rights and define what that looks like for the future. Even though the United States has been complicit in a lot of abuses around the world. To me, that's still its primary responsibility and legacy, at least of its people, to push on themes of civil rights and push the world towards a better place. And that's why I think it's important for Americans to realize that the next civil rights fight that we have to engage in as a people is addressing how these technologies are manipulating us and altering our outcomes in so many unprecedented ways. I think we're just starting the conversation about what conditions these technologies have enabled in our world.

Younger people like me, we're born into this technology. We see it as inevitable or as a linear sort of arrow that goes just in one direction. But the reality, when you look at it, is that the technologies we've developed are determined by our investment. Our investments have been, largely, on defense applications, and that reflects the world we live in. So now I think people should know that they're living in a militarized, surveilled world that is increasingly authoritarian, and could lead to the punishment and tracking of future generations and even their children.

What needs to happen is a sort of a process of understanding how much data has been collected, and how much it has been used against you.

Another scary but important read

PALANTIR is creating the environment for *1984* in America.

As a Brit I don't want PALANTIR involved with our NHS DATA.